Editorial

Identities are constructed from far more than just the ocular. What we see often pervades our immediate understanding, we fall in love at first sight, yet we know that our comprehension of the world is informed by all of our senses. Historically both illustration, and to a lesser degree animation, have been concerned with what is immediately visible. The research projects selected for the inaugural edition of Dialogues, recognise the difficulty of relying solely on visual recording to explore and represent something as complex as identity. Whether attempting to understanding who we are or the landscape we inhabit these projects present an expanded and trans-disciplinary approach to illustration animation research methods.

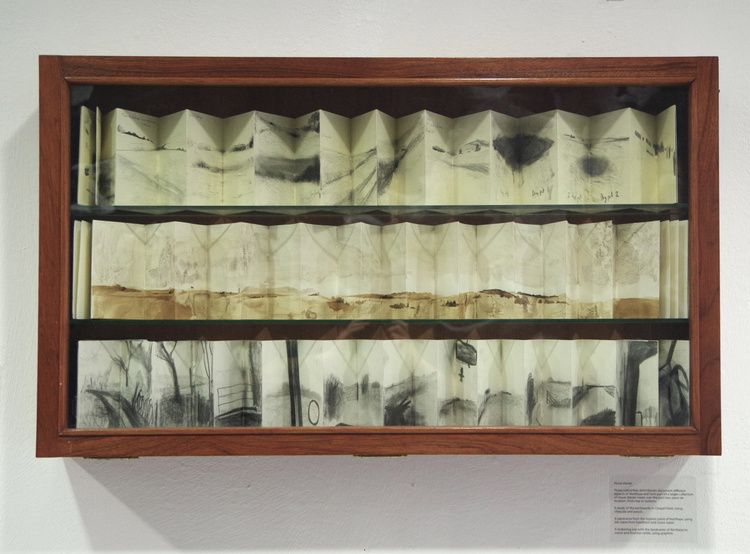

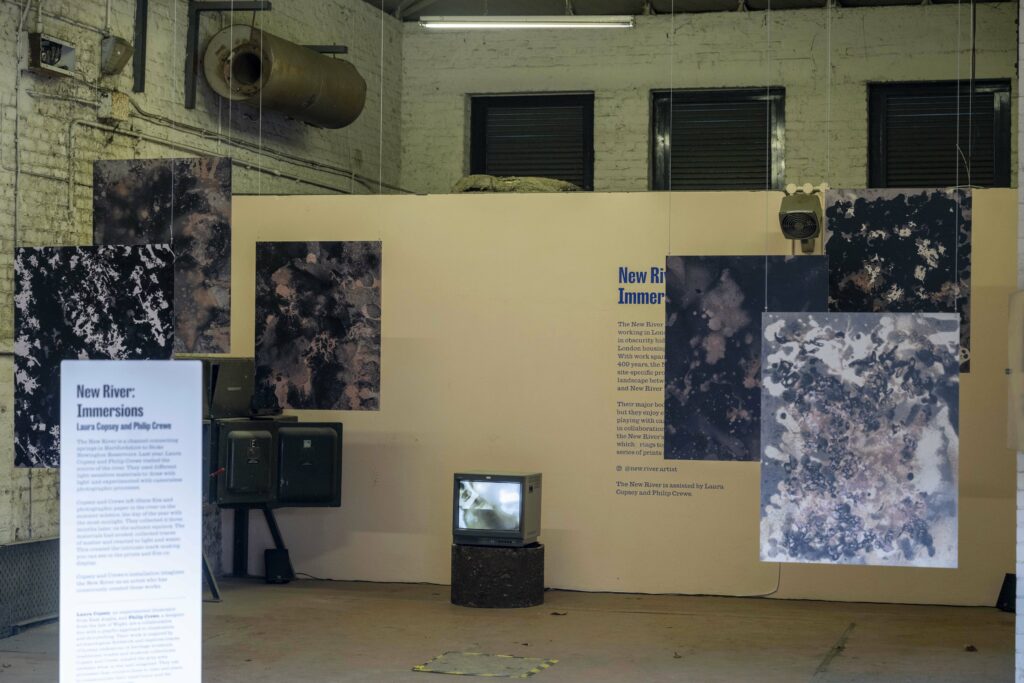

In Leah Fusco’s (Course Leader MA Illustration and Associate Professor) research she positions illustrative documentary as interpretive taking a multi-method approach to visual enquiry, drawing upon methods that sit at the intersection of illustration and humanities disciplines such as archaeology, cultural geography and heritage studies. Drawings on site, underwater camera recording, soil sampling and drone mapping are used to understand the distinctive and shifting identity of the landscape surrounding Northeye, East Sussex. The New River Folk Museum, exhibited at Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration explores the heritage of the New River, London, by discovering the lost identities of working class trades people, omitted from the New Rivers official history. Laura Copsey (Lecturer in Illustration Animation) and Philip Crewe use para fiction, the grey area between the real and unreal, fact and fiction, where imaginary identities intersect with real people to create historical characters who speak to our contemporary interests and concerns.

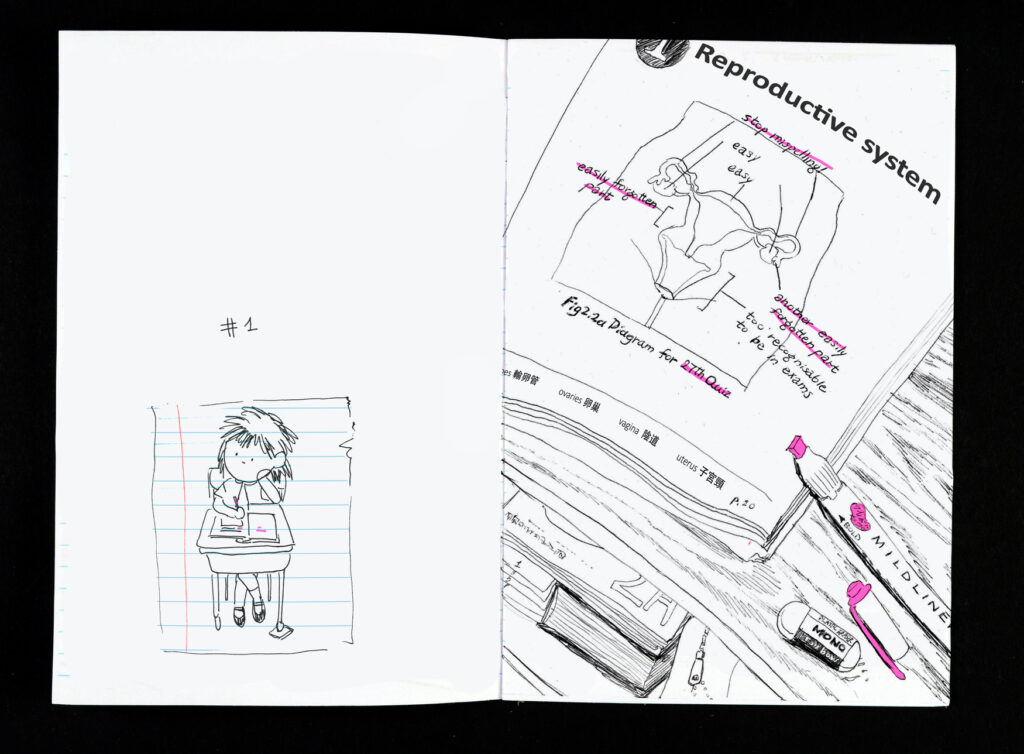

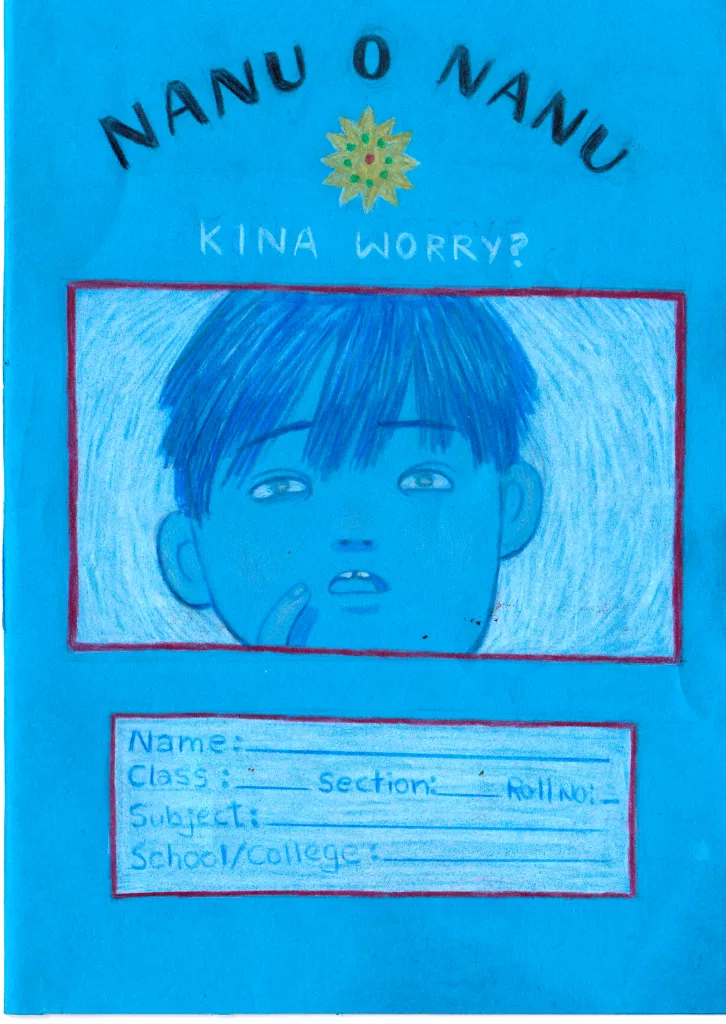

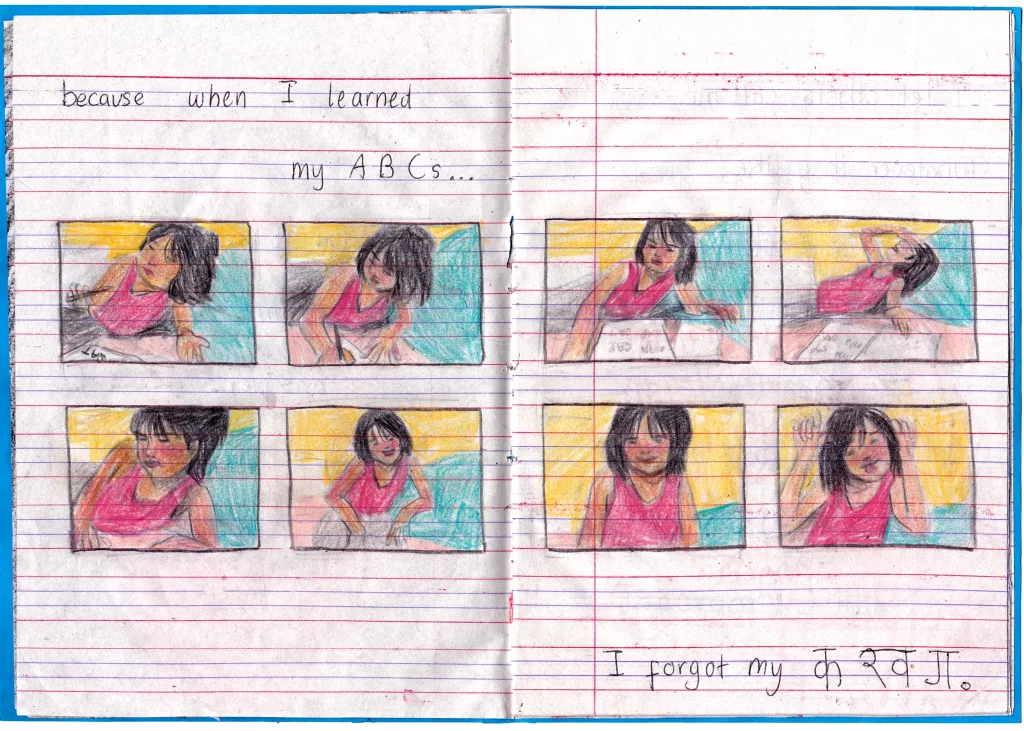

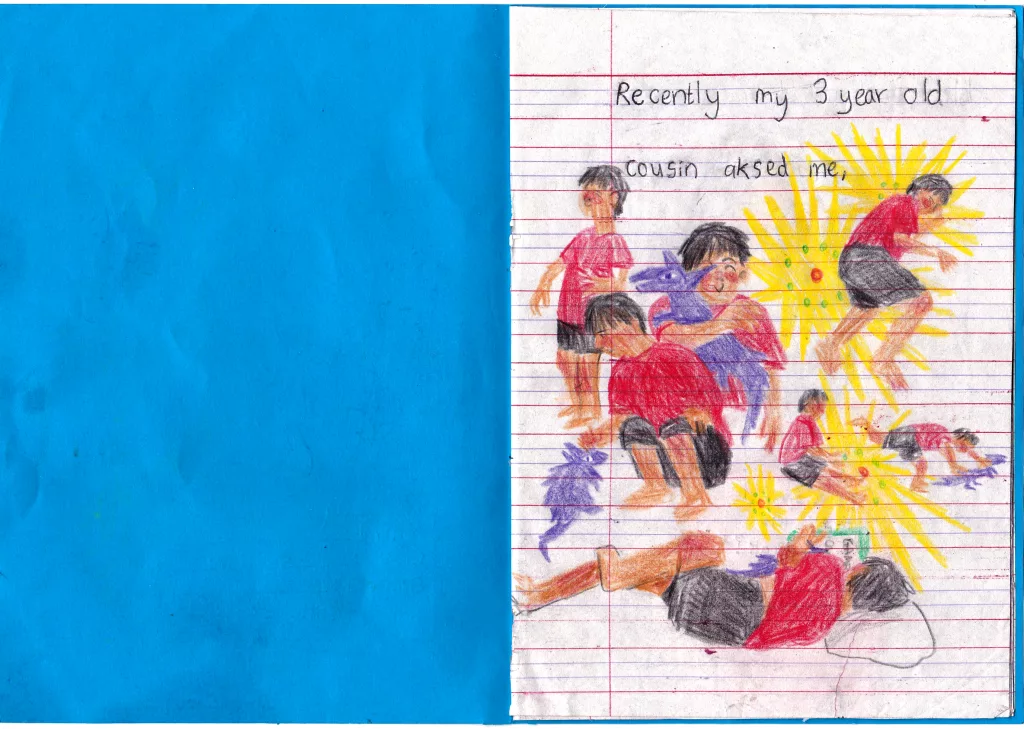

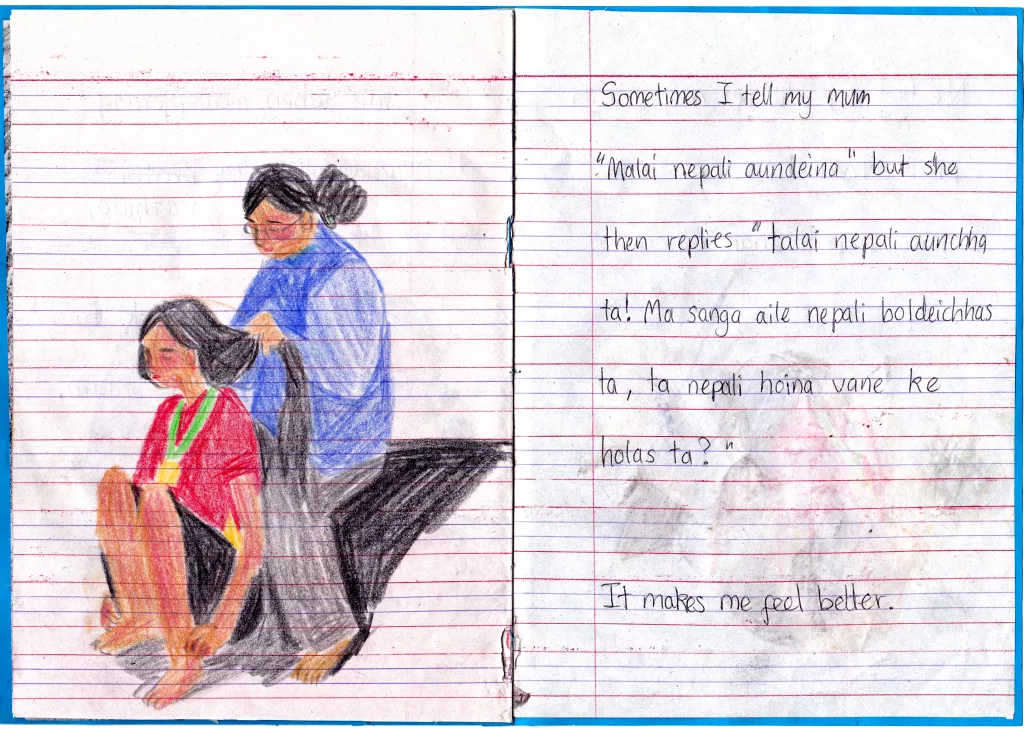

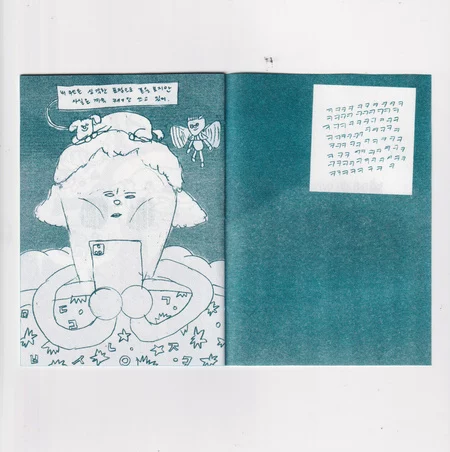

The two assignments in illustration animation education provide students with the opportunity to explore and communicate their own individual or collective identities. These projects use illustration animation methods to document the intangible; examples of cultural heritage, oral histories or collective interests. Outcomes have explored subject matter as diverse as the unspoken rules of South Koreans in everyday life to learning the Nepalese language as a child of second generation migrants.

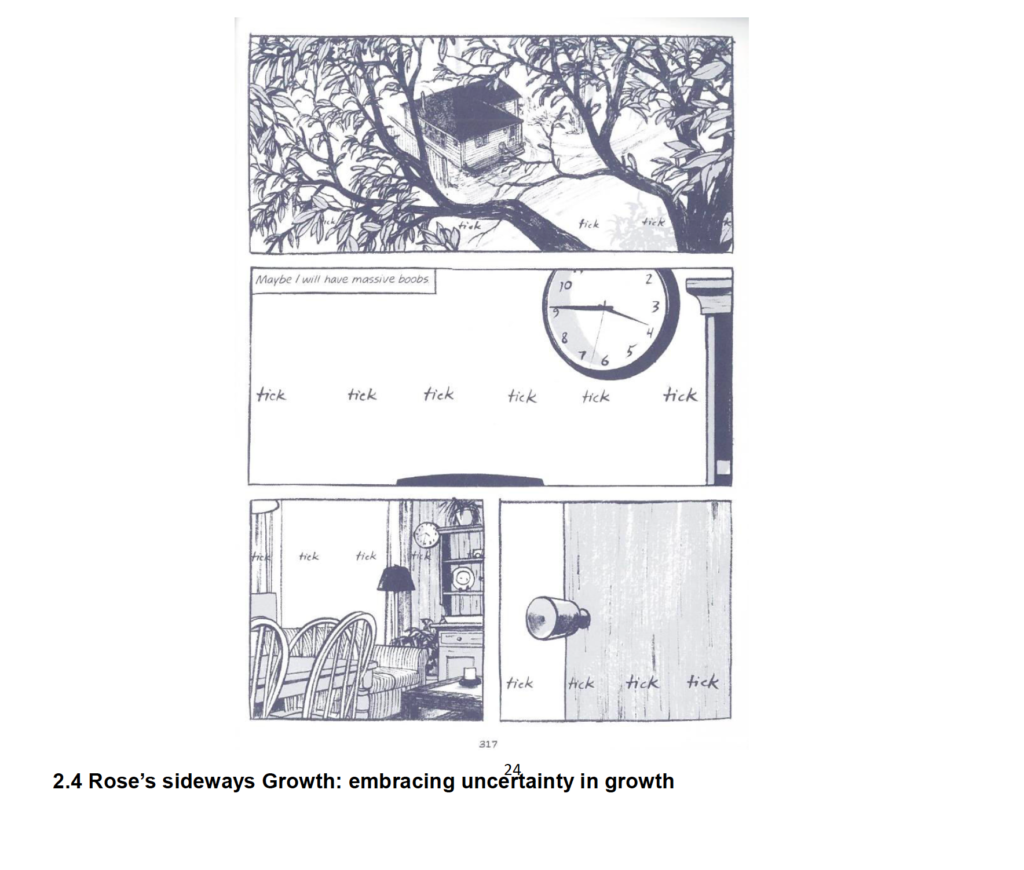

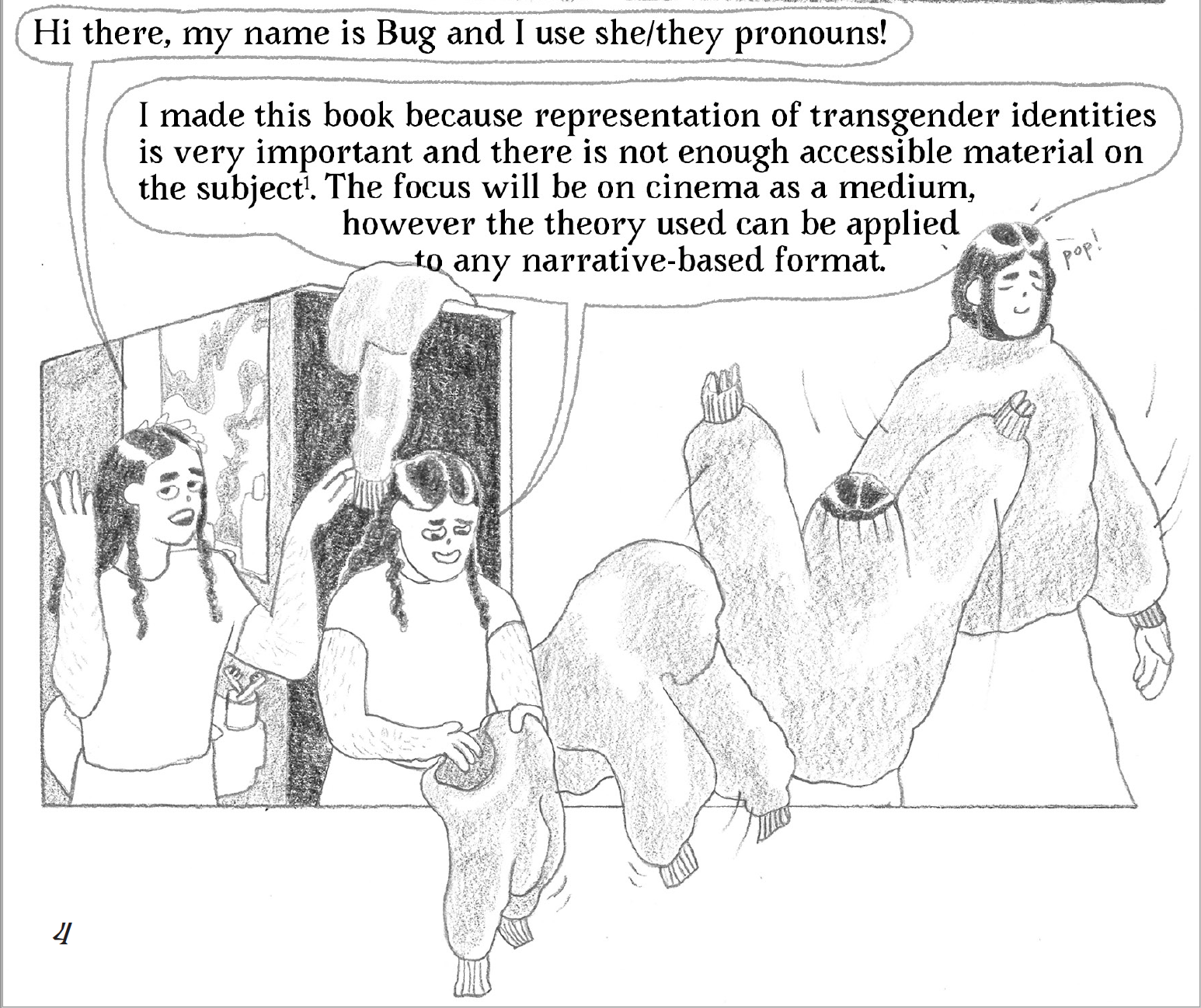

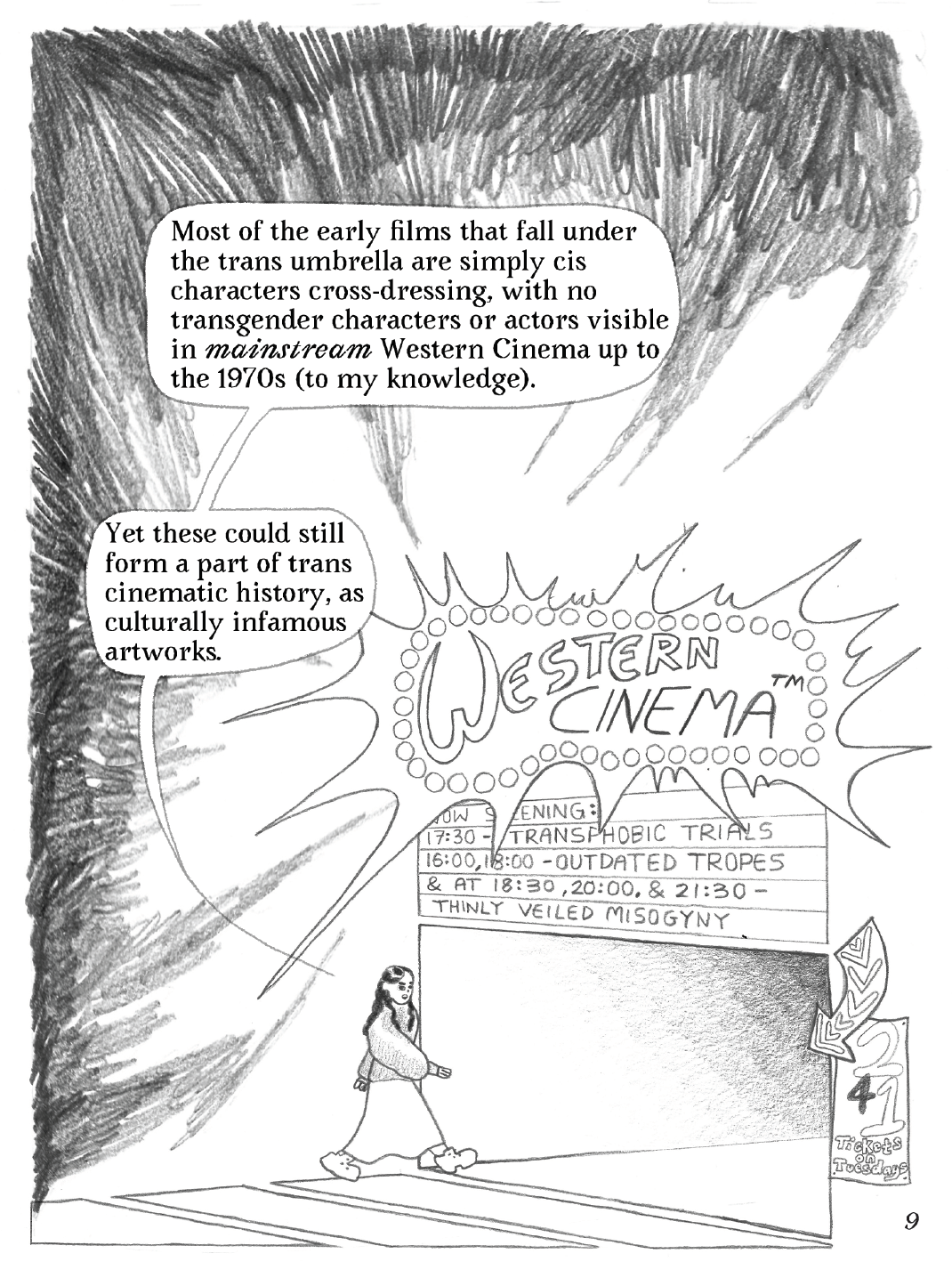

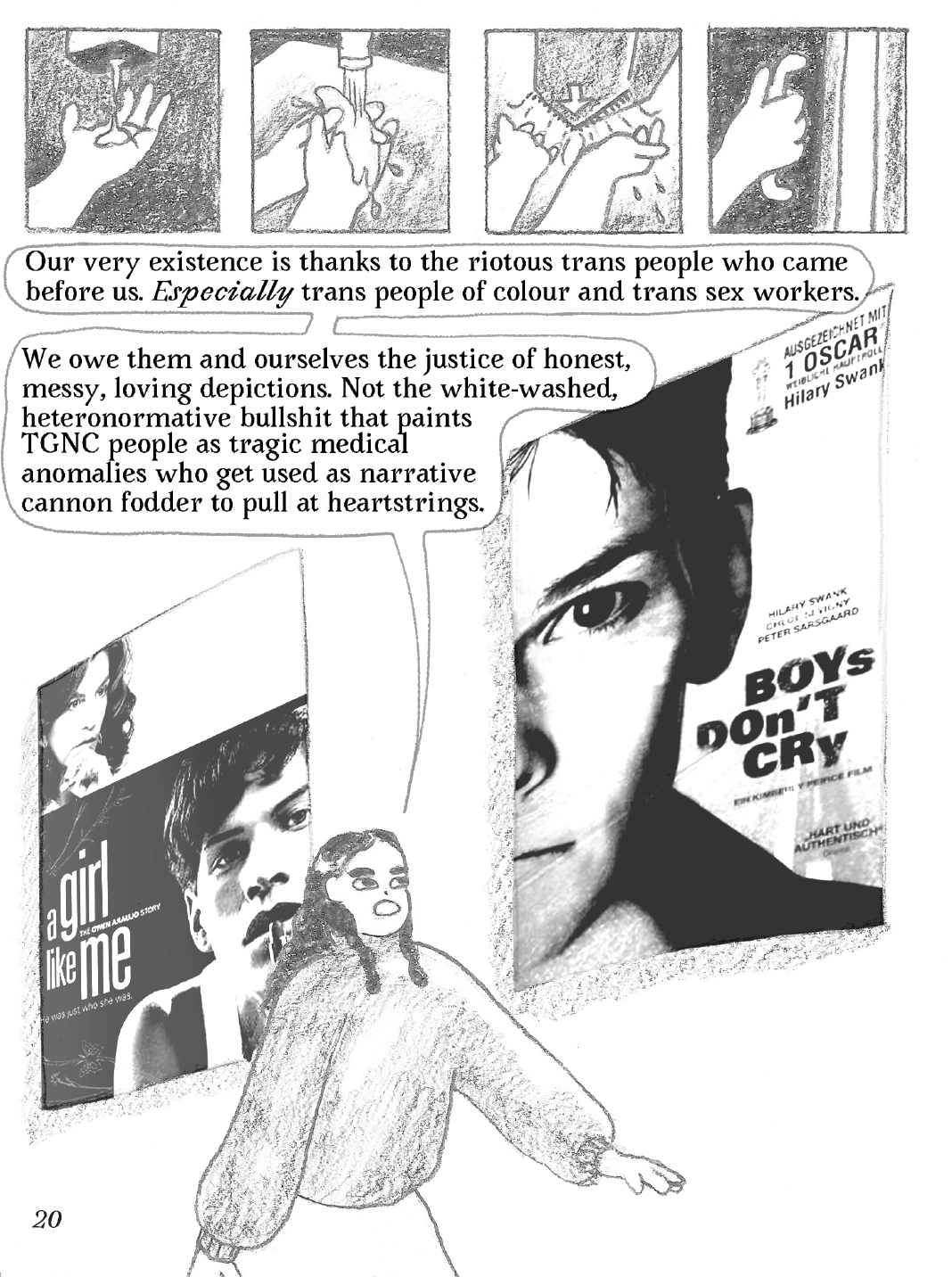

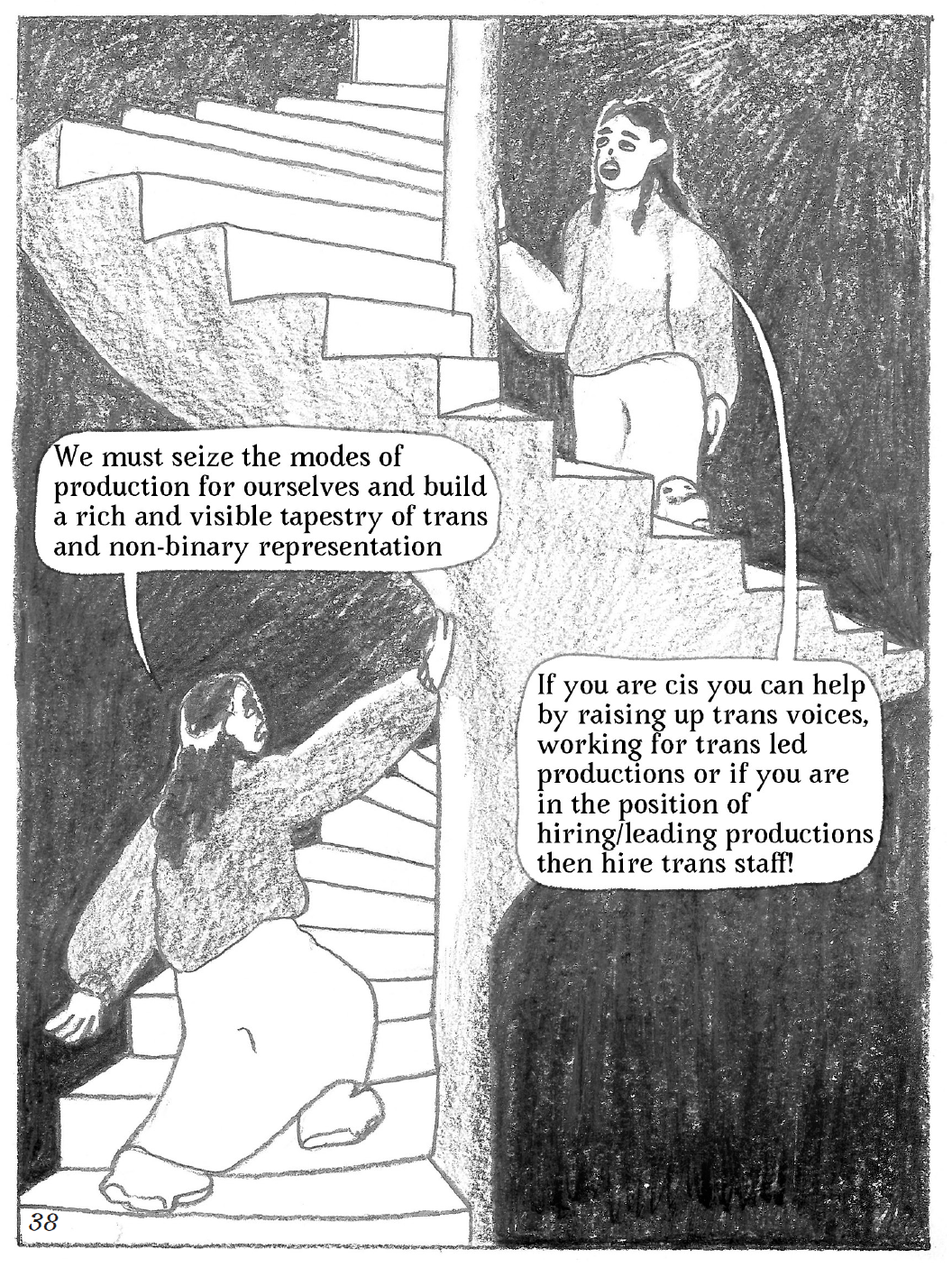

Gabriel Lui (alumni, 2022) takes a norm critical approach to the contemporary experience, identity and visual representation of adolescent girls. Using the idea of ‘sideways growth’, which is rooted in Queer theory, Lui aims to deneutralise western normative beliefs of growth, and in turn suggests an approach to visual representation the helps us rethink the grand narrative of ‘growing up’ encouraging us to look again at ‘the uncertain, the illegible the childish, the failed and the Sideways.’ Bug Shepherd Baron’s (alumni, 2022) 64 page illustrated essay and graphic narrative, Through the Vitriol, explores a trans perspective of the gender non-conforming representation seen in animation and film. This publication extends our understand of how we might communicate new knowledge beyond the written word by offering an alternative to the conventional essay through a compelling combination of images, first person narration and critical analysis that encourages readers to participate and examine film for themselves.

These research projects ask questions about the methods we should use to document, analyse and understand identity. They lean in to the inherent complexity of visually representing identity, resisting what author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie describes as the ‘the danger of the single story’, and emboldening us to embrace inventive research methods.

2022

-

Rachel Gannon is Associate Professor and Head of Department for Illustration Animation at Kingston School of Art.