Mediatisation

The Mediatisation Strand approached lettering, typography and typeface design as mediums in graphic design. We asked how type operates not just as form, but as medium—shaped by, and shaping, its conditions of production and reception. Building on a rich body of research (formal, technical, historical, media and critical theory) the Mediatisation Strand examined three distinct but overlapping approaches to typography: type as communication; type as representation; and type as mediatisation.

Type as Communication focuses on supporting reading by selecting typefaces and setting typography that facilitates engagement with a text, such as in book typography, information graphics, and way-finding.Students investigated how typography mediates meaning and influences perception across different contexts.

Type as Representation emphasises the formal aspects of letters (shape, size, colour) and how they can communicate independently of the sign’s phonetic/textual meaning. It is often used for short texts, such as book covers, movie posters, and logos, to grab attention and appeal to the senses through graphic connotation and iconic signs.

Type as Mediatisation attends to the technical media involved in the production of the design, often transforming utilitarian signs and symbols associated with production into cultural signs and signifiers. This method points towards typography as a medium itself and can be extended to understand how society operates as a mediated construct.

Through this exploration, students have gained a deep understanding of how typography functions as a critical medium in graphic design and how they can direct their practice with both purpose and intent.

What follows is a conversation between Lucia De Francia, Matthew McGann, Poppie Davies and Marcus Leis Allion that took place at the end of the project. The text was transcribed from a recorded dialogue and edited for clarity, flow, and concision. The original voices have been preserved as closely as possible.

Marcus: As you’ll know, I often introduce terms from my research. Has working with the concept of mediatisation shifted how you understand your own practice, or the role of design more broadly?

Poppie: Yeah—it got me to think beyond just flat visuals. To ask, what’s behind the form? What context shaped it? What does it circulate through?

Lucia: It changed how I thought about process. I’ve always struggled with valuing experimentation. But through the strand, I started to realise that it isn’t wasted time. Even the bits that don’t end up in the final outcome still matter.

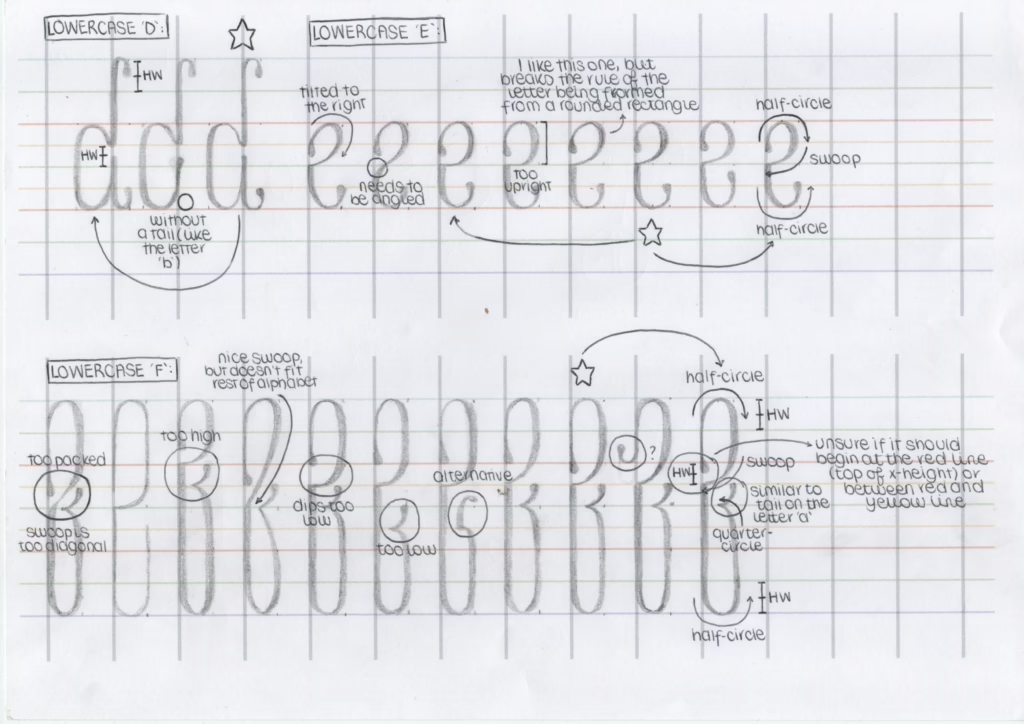

Marcus: That really comes through in your work, particularly your sketchbook, which is full of detailed developments and annotations. There’s a clear intention that’s explored through drawing. It’s a wonderful object in itself—it reveals the tools and methods behind the outcome.

Lucia: I hadn’t really shown it to anyone before. I was just doing it. But then I realised—oh, this is actually the work. It’s not just prep for something else.

Marcus: And your process shifted, more open, less efficient, maybe, but richer.

Lucia: Yeah. At one point I tried to design every letter using one rule. One system. But some just wouldn’t fit. And you said, ‘sophistication is about supporting difference and complexity over uniformity.’ That changed how I saw it. I needed to loosen the system, let the work develop with some flexibility.

Marcus: There’s value in strict models—but ideals can become totalising if we’re not careful.

Matthew: I see my work as more of a constellation—things pop up, and I just keep collecting them. I’m not too worried about where it’s going. It’s about seeing what happens, then joining the dots.

Marcus: Much of our work this year unfolded through co-learning—through shared enquiry, informal teaching, unstructured critique. What did you discover through these moments that might not have emerged in more structured settings?

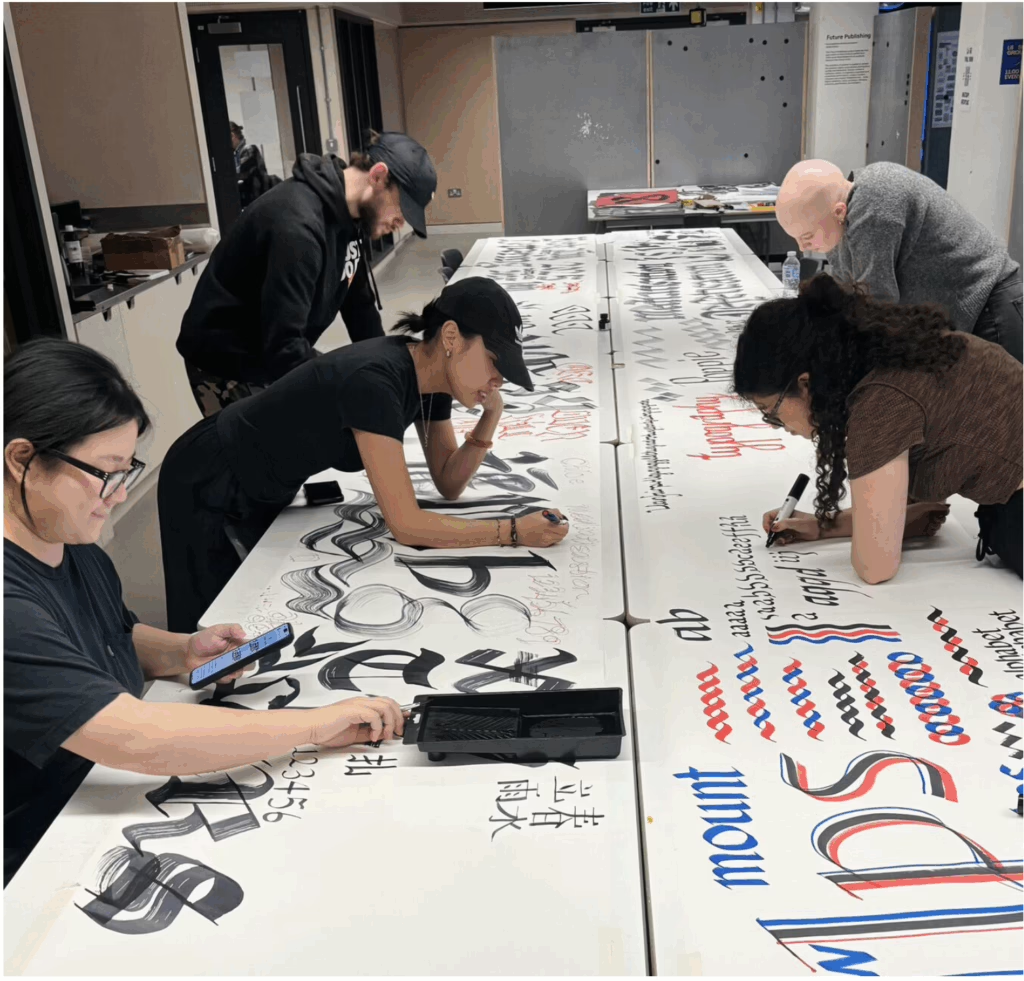

Lucia: The notion of workshops being developed with and co-run by students changed everything. I’d always approached type through calligraphy, but only privately. Sharing that knowledge—making worksheets, talking through tools—made it real in a new way.

Matthew: Yeah, we weren’t just following—we were discovering it together. Everyone had something to offer. Different materials, different approaches. That community was important.

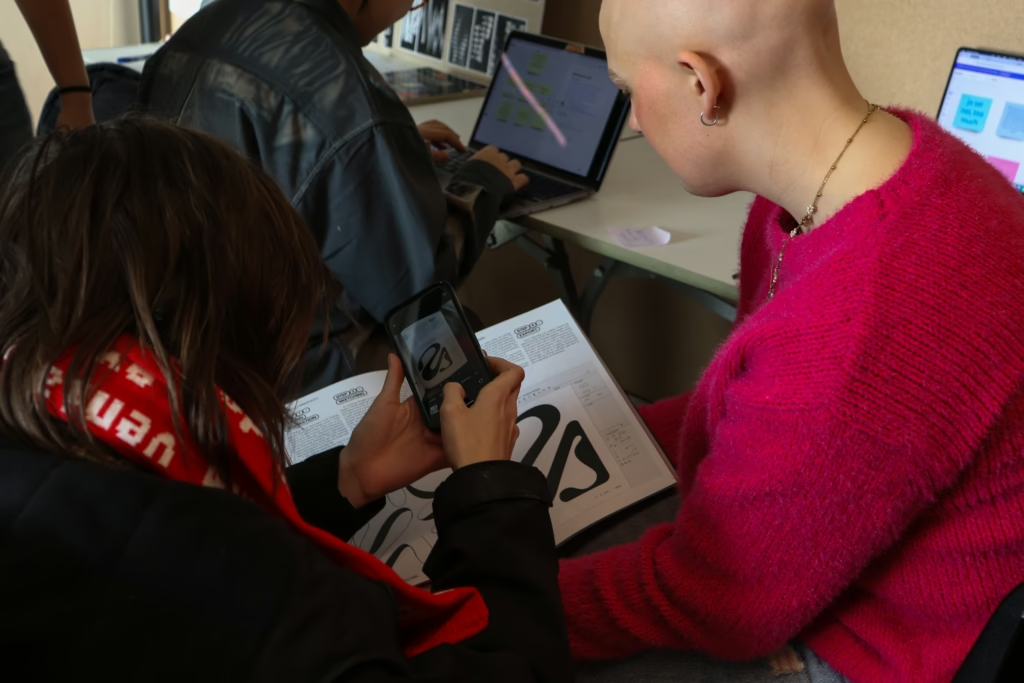

Poppie: We did our own Glyphs Application workshop before the taught one. We just opened the software and sat around, clicking things, getting stuck. And then Matty ran off to get Lucia’s worksheets from the calligraphy session. It actually helped.

Matthew: I remember everyone staring at their screens like, ‘What the hell is this?’ And then Ezra jumped in and started showing people how to draw in pixels. We were just figuring it out. That’s what made it stick.

Marcus: That kind of co-learning builds confidence. It’s folding of a transmission model of communication with a ritual one—it produces knowledge in relation. Is it possible that learning arises less from instruction and more from presence—being with others in a shared space of uncertainty, tools in hand, ideas in motion?

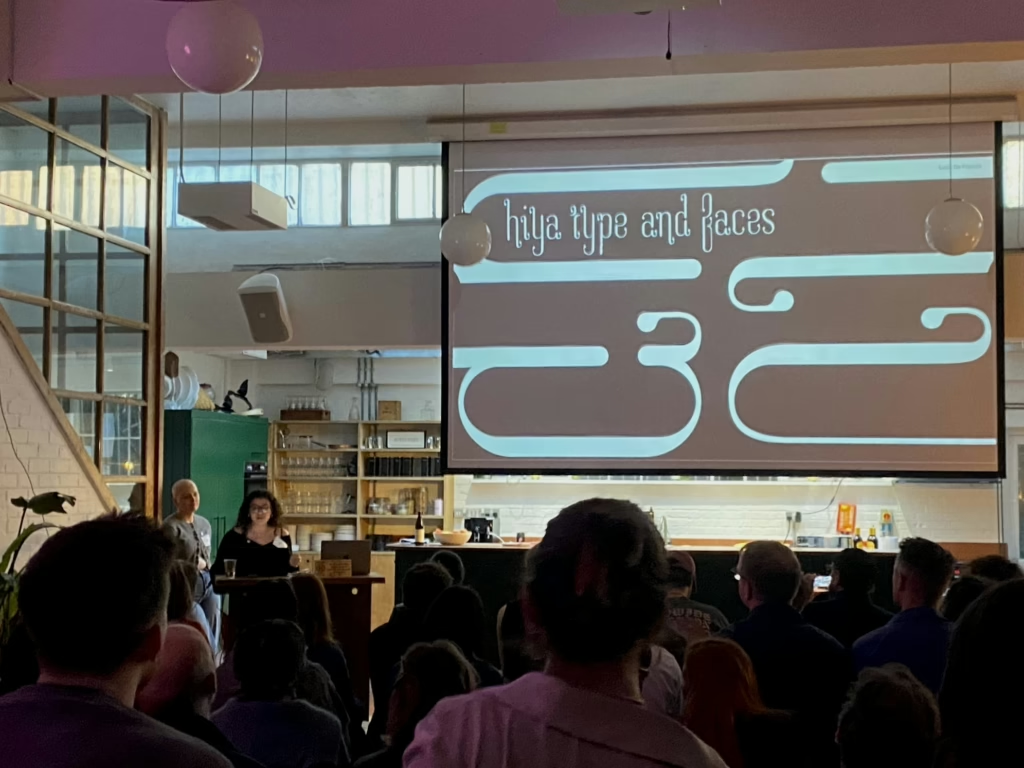

Lucia: Yes. It was the same with Type & Faces. I remember thinking: I don’t want it to be a tutor emailing them. I wanted it to be us, saying—we’re students, we’re serious, we’re here. I think that mattered. It changed the dynamic.

Poppie: If Lucia hadn’t invited us, I don’t know if I’d have gone. But because it came from her, it didn’t feel like ‘industry’—it felt like community. And when we got there, we were treated like peers. Not juniors.

Matthew: We showed our work to people in the industry. It wasn’t about being students—it was about being part of a wider conversation.

Marcus: That was an important initiative that elevated your projects significantly — on your own terms.

Lucia: Yeah—and just being in the room. Showing something and having people respond. I used to think I had to justify everything. Now I trust the work, and let the meaning come later.

Marcus: We’ve engaged with a number of processes and methods, not only formal and technical, but also paideutic (a mode of learning concerned with formation, reflection, and critical becoming). Do you have thoughts about that?

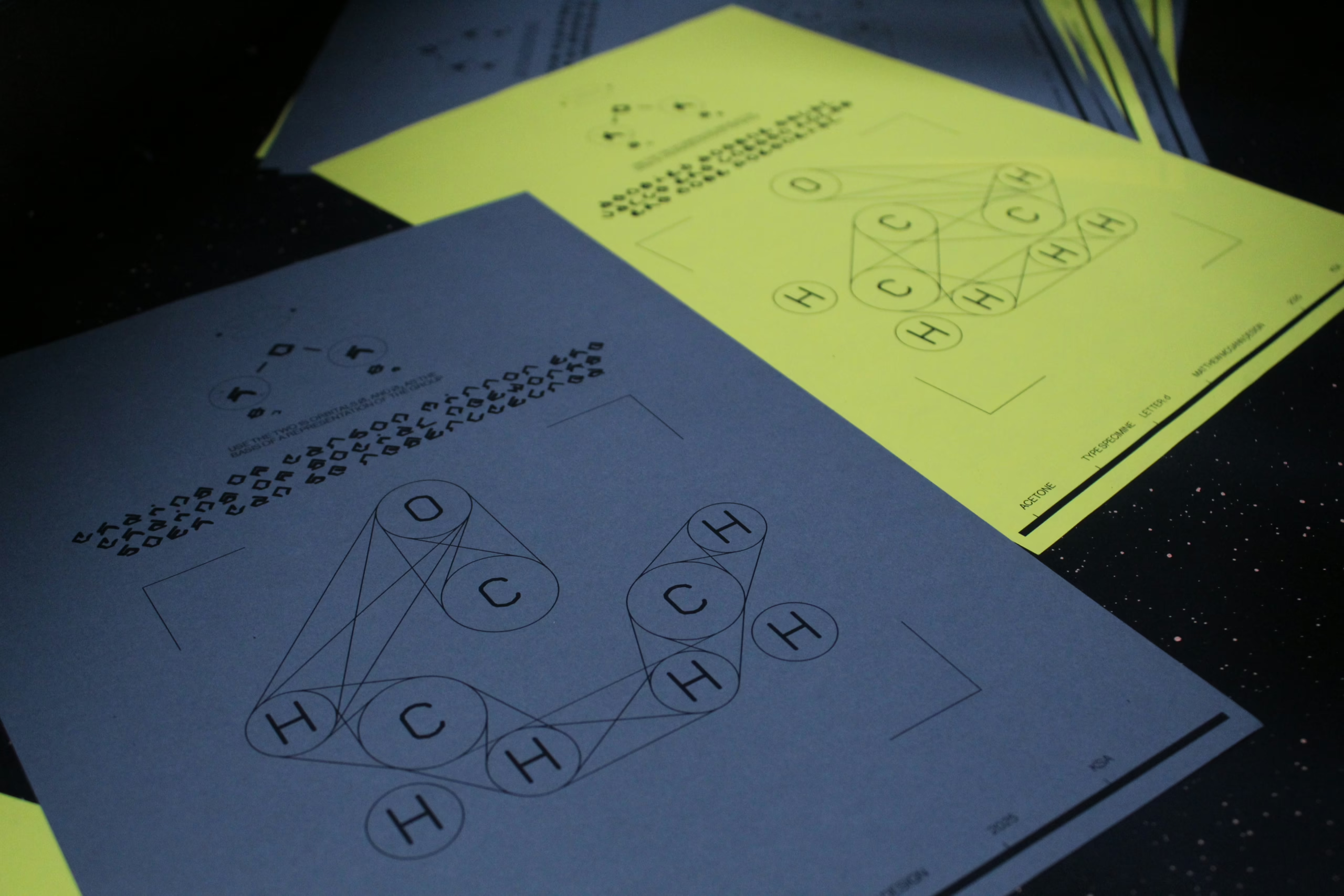

Matthew: My typeface came from graffiti and community. It’s called Molecule. I was thinking about atoms, and how we come together. In a perfect world, my friends from Salford would be designers—but they’re not. They’re in warehouses, kitchens. So I wanted to show that you can start from anywhere. Use free software, draw it by hand, build something. You don’t have to be rich to do this.

Marcus:You were visualising your politics—countering atomisation by designing collectivity. And the way you all supported each other this year felt like a version of that. Small bonds forming into something larger.

Matthew: Yeah—and also, at the start of the year, someone in the group was trying to base their typeface on Off-White. I remember thinking, like—it’s too corporate. We can go deeper than that. That was one of the moments where I realised I wanted my work to push back, not just replicate.

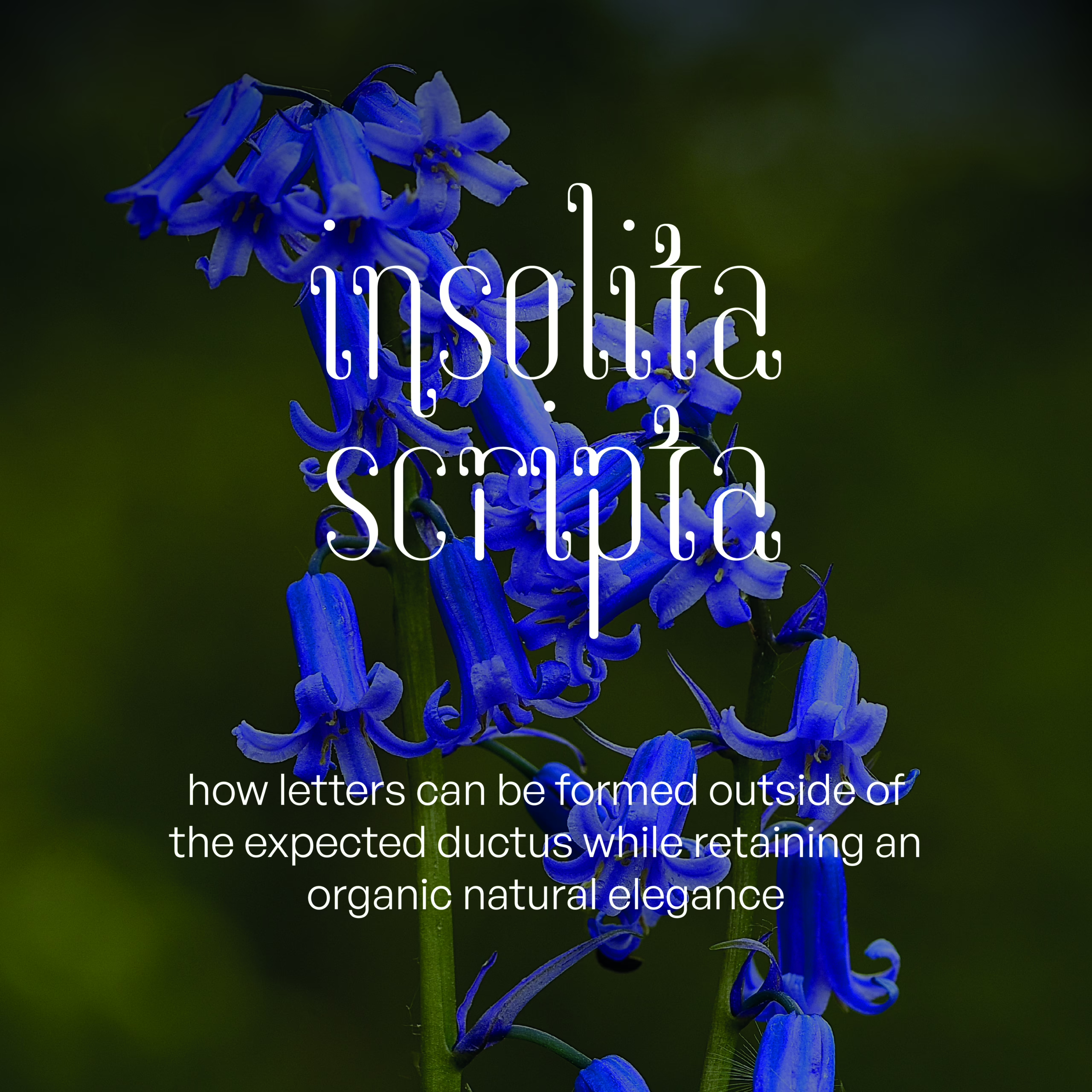

Lucia: Sometimes it’s more intuitive. I added ball terminals to my typeface because they just felt right. Later, when I looked at the full set, I realised—this looks like bluebells, leading to an investigation into how I could situate my typeface within the language used in botanical studies. It wasn’t planned. But it made sense.

Marcus: That’s often the case I find—form comes first, and then through dialogue with others (either in person or through reading), language helps us articulate our intentions—a dialectic dance of practice and theory.

Lucia: Yes. You follow the instinct. And later, you find the words for what you were doing all along.

Poppie: For me it was Welsh language and feminist publishing history. That started in my IRP, but it shaped everything—my strand project, my Design Studies work. Research and practice are totally interlinked now.

Marcus: You each began the year with a proposal—a kind of pre-emptive model of what the work might be. But practice rarely follows a straight line. How did your project shift in relation to that original intent? Do you see your project as closed, complete—or still in motion? What are you carrying forward, not as outcomes, but as ways of thinking or making?

Lucia: Honestly, I forgot my research question halfway through. When I looked back, the work I was creating actually fit. I’d answered my question—but not how I’d expected to.

Poppie: It’s about accepting that there’s no ‘final’ version. Research interests grow. The project keeps unfolding. And that’s OK.

Matthew: I started with experiments—then realised I hadn’t done any research. I went back, found Armin Hofmann, and that clicked with the molecule stuff. Suddenly everything joined up. Like, I’d done it in the wrong order, but it worked.

Marcus: That’s fascinating—especially from a digital media perspective. Your process sounds a bit like a diffusion model: everything happening at once, only beginning to cohere towards the end.

Poppie: Exactly. It’s a process of discovering what the work is really about. And that process doesn’t end here.

Lucia: What I’m taking forward is being more conscious of the people and ideas around me. Not just working in a bubble. Building community, being present, listening.

Matthew: Same. And knowing that you don’t have to be rich or well-connected to do this. Just curious. You can start anywhere. And you don’t have to do it alone. And I want to carry that forward. Keep the connections going. Keep the molecule growing, basically.

Marcus: Exciting. That’s what the Mediatisation Strand sought to model: design as an enquiry into modes and relations of production. Approaching graphic design through research helps us move our practice away from immediacy and instrumental thinking. Thank you all for your time.

The Mediatisation Strand was enriched by the insights of many informed and interesting people, in particular Andrew Haslam; Steven Swinney; Linda Byrne; Anne-Dauphine Borione (aka Daytona Mess); Paul McNeil (MuirMcNeil); Luke Charsley; Addison Copas; Guy Burgess; Min-Young Kim, Ksenya Samarskaya, and Alex Slobzheninov at Inscript; Fred Wiltshire and the team at Type & Faces; as well as the wider course team and student community.

Mediatisation Strand 24/25 was: Annie Liu, Cerys Fitzpatrick, Chloe Chen, Esther Cheung, Ezra Bagheri, James Medcraft, Krisite Pang, Kylie Wong, Lily Clowes, Lucia De Francia, Matthew McGann, Poppie Davies, Rebecca Su, Ying Gao and Marcus Leis Allion.

Marcus Leis Allion

Marcus Leis Allion is a typographer, educator, and researcher. His work spans critical pedagogy, poetics of aesthetics, and the historical materialism of visual culture.