Growing sideways in the vertical

An analysis of representation of the growth in adolescent girls in This One Summer (2014) and Water lilies (2007)

Student Dissertation extract

When I was growing up, every teen media seemed to be telling me that when I became a teenage girl, I will “become more girly, less childish and fall in love with a boy”, so that was what I believed. But as I got older, none of that happened. Indeed, “I will like boys” gradually became “I might” and then into “I don’t”. It seems like I have fallen off the trajectory of my own growth. So, what has happened to my growth? Where has it gone? What happens to the other girls like me? Do we ever grow up? In this essay, I will explore the representation of adolescent girls ‘alternative ways of growing in Mariko and Jillian Tamaki’s comic This One Summer (2014) and Céline Sciamma’s film Water lilies (2007). To do so, I will apply the framework sideways growth. It is rooted in queer theory, a deconstructive strategy that aims to denaturalise1 heteronormative presumptions of different social issues’ (Sullivan 2003).

Sideways growth specifically aims to denaturalise the Western normative beliefs of growth. It identifies what is considered as normative growth, and reframes what is being left behind as equally valid growth. Although the concept was first proposed by Stockton in 2009, it was not until 2021 that Malewski’s study has tried to create its working definition. Therefore, in this essay, I would like to adapt and apply this new framework into my two case studies to explore its potential. My first case study is This One Summer (2014), a 319-page graphic novel written by the Canadian illustrator Jillian Tamaki and writer Mariko Tamaki.

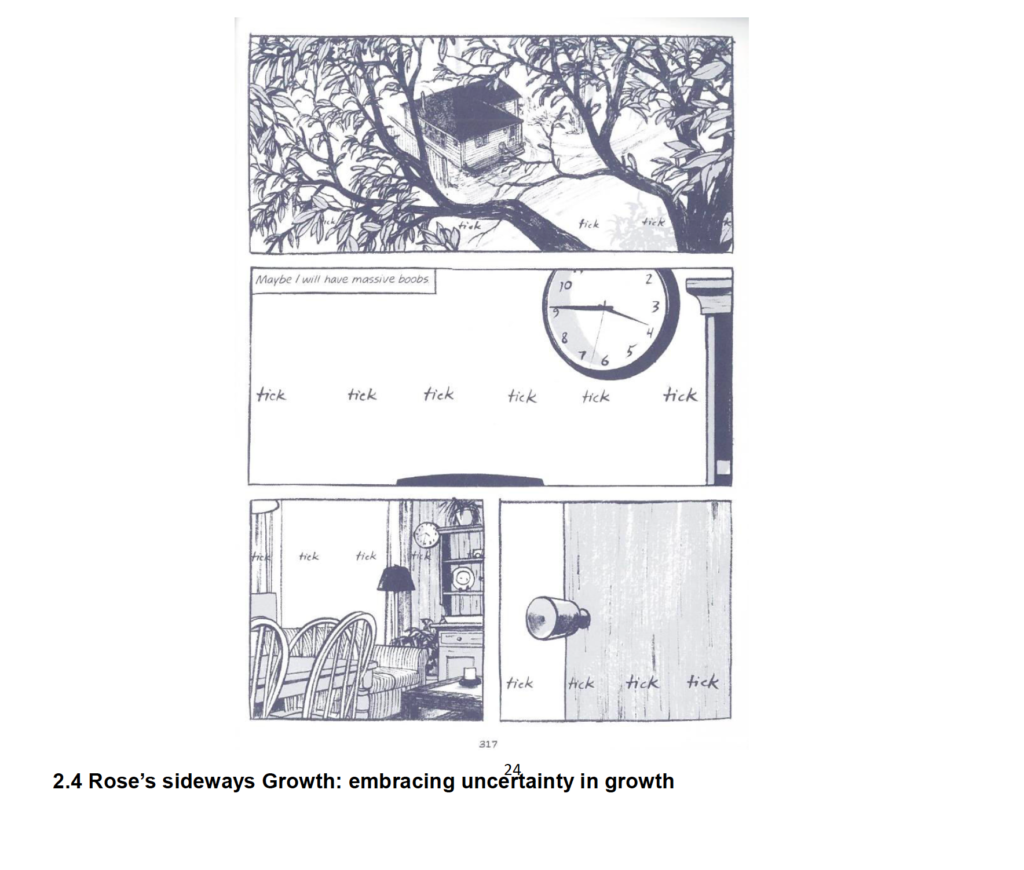

It is a coming-of-age story about Rose, an early adolescent girl, who observes the “adult world” around her. My second case study is Water lilies (2007), an 85-minute film by the French director Céline Sciamma. It is also a coming-of-age story, but with three slightly older 15-year-old protagonists: Marie (Pauline Acquart), Floriane (Adèle Haenel) and Anne (Louise Blachère). It focuses more on the desire and relationship amongst teenagers. Both works are small character studies: they have a slow pace and follow mainly one character’s subjectivity within a short span of time in just one location. They put the representation of adolescent girls’ experience into the centre and highlight the less obvious, but still important, progress of growth. Despite having different mediums, geographical settings, and focuses, I believe they depict adolescent girls’ alternative growth in similar ways. I first connected the two works together because both received similar criticisms from mainstream review websites Rotten Tomato and IMDB, regarding a lack of “character development”. Yet, it was the characters’ growth that most charmed me, though I could not articulate why: Is there really a lack of “character development”? How do the works represent the growth of their adolescent girls’ protagonists? Why are their growths not being recognised? Chapter 1 establishes the framework of sideways growth through examining my key texts. I will also relate the framework to female adolescence or girlhood. Chapter 2 analyses the narration style and layout in This One Summer to understand how it develops one adolescent girl’s sideways growth by focusing on her inner thoughts and past experience in upwards growth.

Chapter 3 explores how metaphors and cinematography in the film Water Lilies help represent three girls indifferent stages in their adolescence, navigating through their current struggles within the upwards growth and their subsequent sideways development. My study is important because as Trites (2014, p.147) argued, “(w)e replicate scripts of growth to organize our own experiences of growth, to organize our understanding of other people’s growth.” Media representations of girls influence how the general public and the girls themselves conceptualise their growth, just like how I did in the past. When only upwards growth is presented as the correct way to grow for girls, it runs into what Adichie (2009, 9:31) called, “the danger of a single story”, an incomplete story that “show a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again and that is what they become”.I believe this study could help identifying the applicability of the new framework sideways growth and raise awareness of the ideology behind it.

…

Conclusion

My dissertation explores how This One Summer and Water Lilies represent adolescent girls’ growth. In This One Summer, by going into one girl’s mind to show her past lingering thoughts; in Water Lilies, by navigating three girls’ current struggles. By being small-scale, both delve into the characters’ subjectivity in details, creating sympathetic representations of the struggles of growth in adolescent girls. Both of them framed the struggles as a consequence of the grand narrative, and create resolutions by letting the characters grow sideways. In doing so, they resist the ‘danger of a single story’. They tell stories that rejects the normative way of growth and embraces the alternative, and hence, reveal that there was never a single correct way to grow. My study suggests that Malewski’s (2021) framework “sideways growth” is applicable in identifying and analysing the representation of adolescent girls’ alternative growth. However, I am aware that the new framework is based on the Western normative belief of growth. Because of this, I have limited my analysis to representation of white, able-bodied girls living in western countries to keep it simple. Nevertheless, as a Hong Kong girl who grew up with Western teen media, I still find the ideology behind this framework resonating with my own experience of growth. I believe ‘sideways growth’ can be adapted and applied to representations of growth of the disabled, other races and cultures, and perhaps could have an even stronger impact on questioning our way of theorising growth. I can conclude there is growth in Rose, in Floriane, in Anne, in Marie, and in me or any other girls like us. It is just obscured by the grand narrative of upwards growth and sideways growth could reveal them again. It helps us rethink what is valuable in the experience of growth, and encourages us to look at the uncertain, the illegible, the childish, the failed, and the sideways.

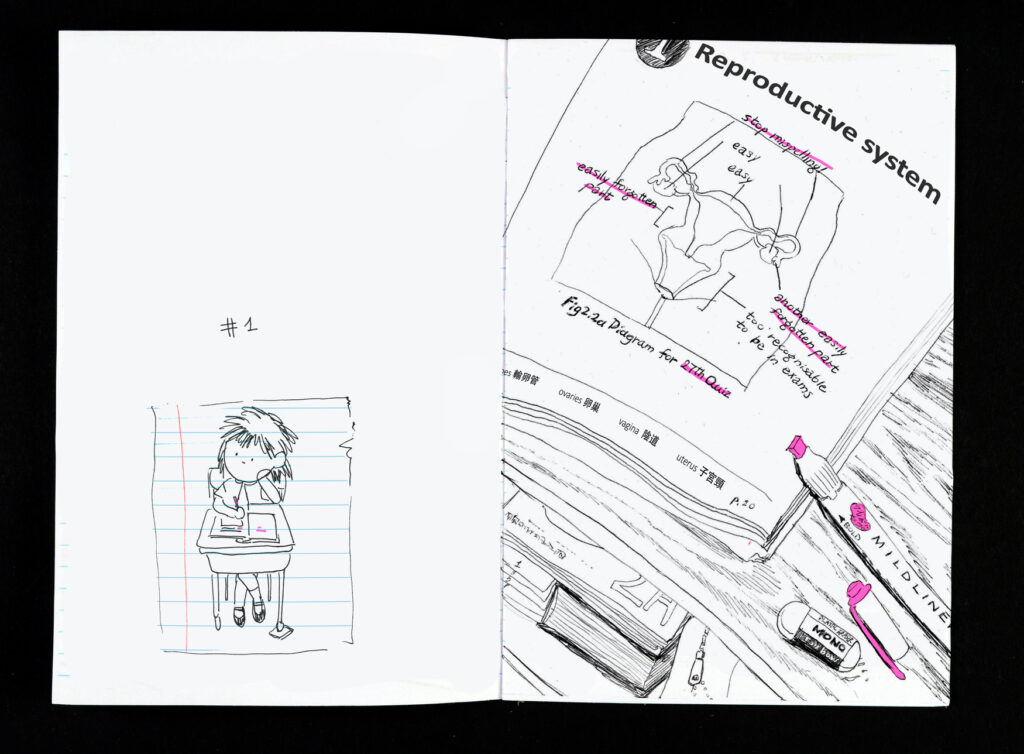

What Was Not Taught In My Sex-Ed

(A project that ‘re-presents’ the themes of the dissertation research)

14x20cm, 28pp, Ball pen and highlighter, digitally printed

A comic that comments on my sex education in a Hong Kong Catholic girl school as a queer girl. Using the format of doodles on a homework book, it focuses on using humour to discuss taboo subjects and appropriating daily visual languages.

- denaturalise is derived from the term naturalise, meaning the process of ‘transmuting what is essentially cultural (historical, constructed and motivated) into something which it materializes as natural (transhistorical, innocent and factual)’ (Hall, 1997, p.181-182, emphasis in the original). Denaturalise means ‘the undoing of the process of naturalisation.